FBI Spent 44 Months Probing Leak To TSG

"Stubborn Ways" focused on classified CIA report

View Document

MAY 17--In response to The Smoking Gun’s publication of a classified CIA terrorism report, the Department of Justice launched a lengthy leak investigation that included subpoenaed telephone records, interviews with dozens of government officials,  polygraph and computer examinations, and “a fair amount of time trying to dig up information about the site itself,” according to FBI records.

polygraph and computer examinations, and “a fair amount of time trying to dig up information about the site itself,” according to FBI records.

The federal probe is detailed--albeit in a significantly redacted fashion--in 682 pages of FBI records released last month. More than 350 other pages related to the criminal probe were withheld in their entirety by bureau officials who processed a Freedom of Information Act request filed by a TSG reporter.

The FBI investigation, run by Washington, D.C.-based counterintelligence agents, sought to determine who provided TSG with a 12-page CIA report detailing the organizing activities of al-Qaeda members imprisoned at Guantanamo Bay (and the U.S. government’s inability to effectively combat these efforts).

The classified document, which can be found here, includes sensitive material from several U.S. intelligence organizations and their foreign counterparts.

The federal probe--code-named “Stubborn Ways”--was launched shortly after TSG’s July 2006 publication of the CIA report. The case remained open for three years and eight months, spanning the Bush and Obama administrations. It was formally closed in March 2010 when, after much internal debate, the Department of Justice’s Counterespionage Section declined to authorize a subpoena--sought by the FBI--compelling TSG’s editor to testify before a grand jury about its source.

During the course of the FBI investigation, agents interviewed 43 individuals, many of whom appear to have been CIA employees stationed at the agency’s Langley, Virginia headquarters. Other interviews were conducted in Boston; Cincinnati; New Mexico; Ohio; Maine; Nairobi, Kenya; and Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

The criminal probe identified “one possible suspect,” an Arlington, Virginia woman who passed a polygraph exam to which she consented. The woman also apparently signed a consent form allowing investigators to search her computers.

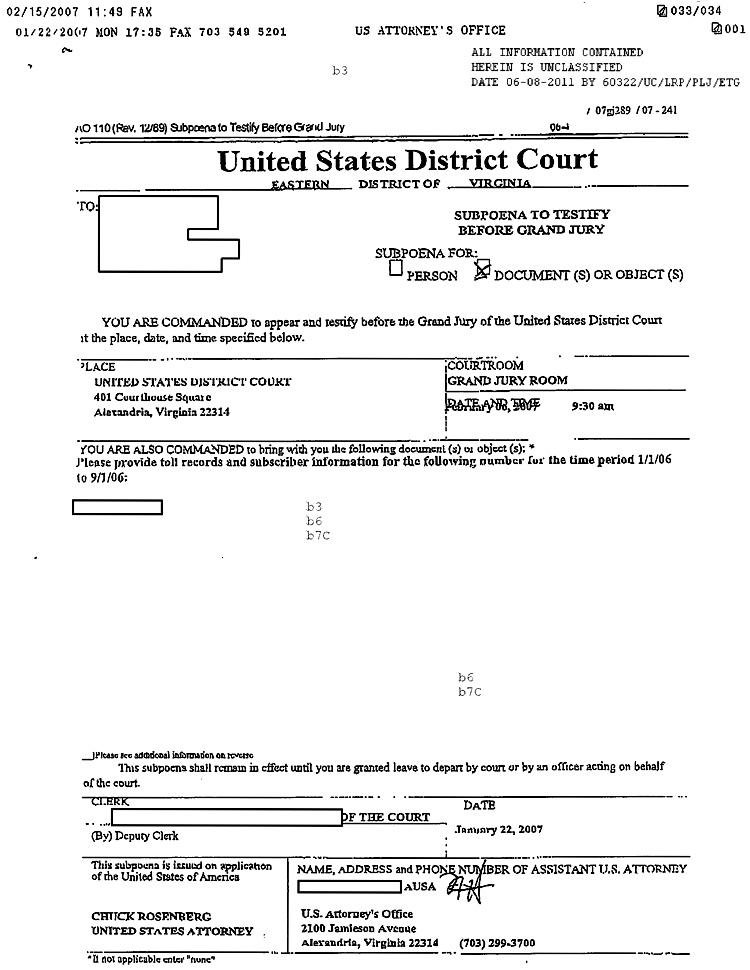

The FBI records show that, during the course of the probe, Justice Department prosecutors issued three subpoenas, at least  one of which sought toll records and subscriber information for a specific telephone, the number of which is redacted from the documents. The phone records obtained by investigators covered an eight-month period preceding and following TSG’s publication of the CIA report.

one of which sought toll records and subscriber information for a specific telephone, the number of which is redacted from the documents. The phone records obtained by investigators covered an eight-month period preceding and following TSG’s publication of the CIA report.

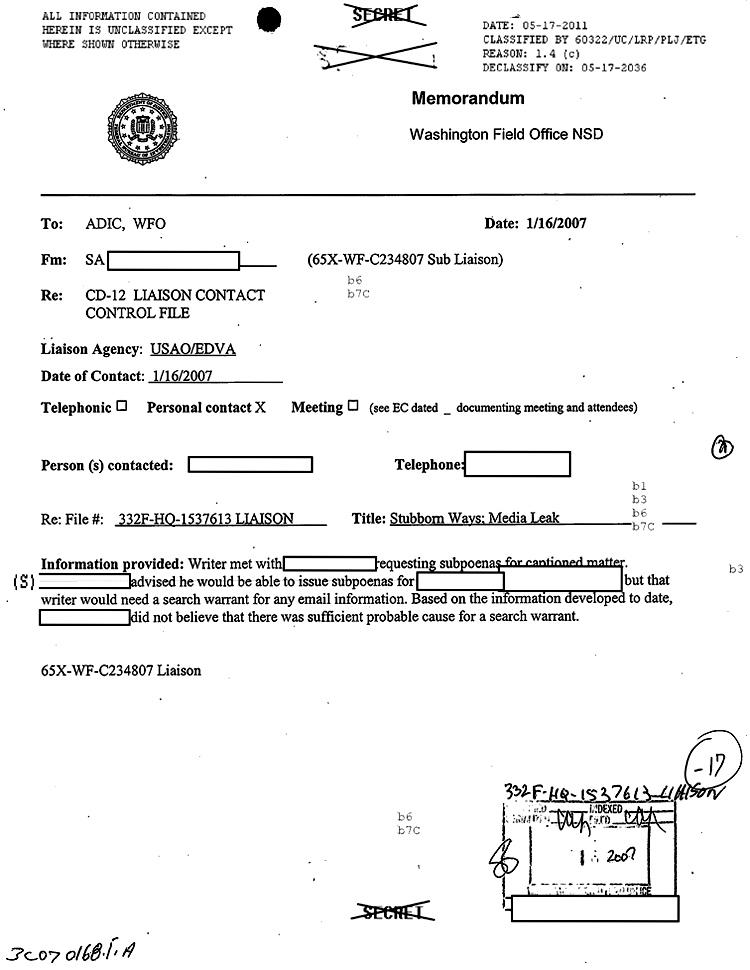

In one memo referencing a prosecutor’s agreement to issue the subpoenas, an FBI agent noted that the government lawyer advised that investigators “would need a search warrant for any email information.” The redacted records do not reveal whose email account was of interest to the “Stubborn Ways” sleuths.

Similarly, the released documents have been purged to remove most details of the subpoenas, including what they sought, to whom they were issued, and what they yielded. However, it appears that the grand jury action did not help identify the leaker. In one memo, the chief of the FBI’s Counterespionage Section reported that agents had “exhausted all authorized counterintelligence leads” and come up empty.

So investigators turned their eyes toward TSG and its corporate parents.

The records show that agents obtained detailed Dun & Bradstreet reports on Court TV, the cable network that purchased TSG in 2000, and Time Warner, the parent of Court TV (which is now known as truTV). Agents also recorded the names of Time Warner’s top executives. In one e-mail, an FBI agent wrote that, “I spent a fair amount of time trying to dig up information about the site itself, but there wasn’t a whole lot other than it’s own material.”

After TSG declined a request from FBI Agent Gregory Leylegian to disclose the site’s source, the bureau asked prosecutors to issue a subpoena directing the site’s editor to testify before a federal grand jury in Alexandria, Virginia.

Initially, Department of Justice lawyers seemed amenable to the subpoena request. According to one FBI memo, a Counterintelligence Section official explained to an agent that “postings to a website have not yet been deemed to carry the same protections afforded to the media. Postings to a website/blog are considered an open question at DOJ.” As a result, the official reported that they were seeking a determination from the department’s Office of Enforcement Operations (OEO) “so a subpoena can be requested.”

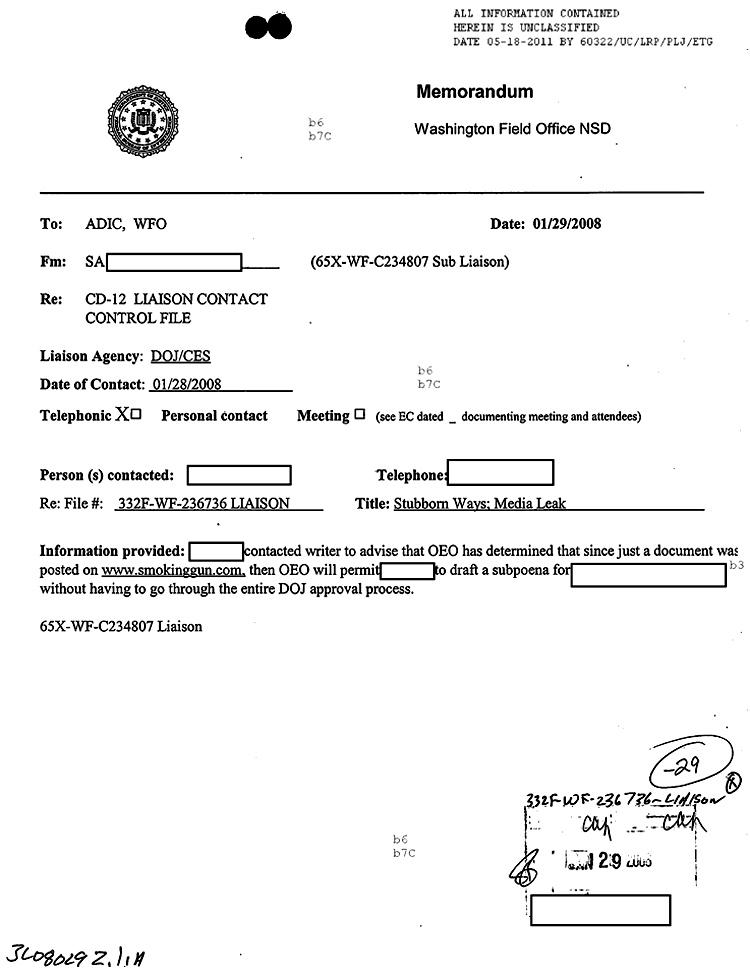

A subsequent FBI memo indicated “since just a document was posted on www.smokinggun.com,” OEO had agreed to permit the drafting of a subpoena “without having to go through the entire DOJ approval process.” [Most references to TSG’s web address in the FBI documents fail to include the “the” in its url.]

A subsequent FBI memo indicated “since just a document was posted on www.smokinggun.com,” OEO had agreed to permit the drafting of a subpoena “without having to go through the entire DOJ approval process.” [Most references to TSG’s web address in the FBI documents fail to include the “the” in its url.]

However, despite that initial approval, subsequent internal Justice Department deliberations stalled the subpoena’s issuance. In an e-mail, an FBI agent described those discussions--and the related exchange of internal memos on the subject--as “going back and forth (and back and forth).”

Finally, after OEO officials told their Counterespionage Section counterparts that they were “no longer in a position to make [the subpoena] decision,” the leak probe reached its conclusion. Left with the responsibility to decide whether to compel testimony from TSG’s editor, the counterespionage officials “ultimately declined to authorize a subpoena.”

While noting that its case could be reopened “if deemed appropriate,” FBI officials closed “Stubborn Ways” in March 2010, about 44 months after opening the leak investigation. (10 pages)