"Witness 40": Exposing A Fraud In Ferguson

TSG unmasks witness who spun fabricated tale

View Document

Ferguson "Witness 40"

-

Ferguson "Witness 40"

-

Ferguson "Witness 40"

-

Ferguson "Witness 40"

-

Ferguson "Witness 40"

-

Ferguson "Witness 40"

-

Ferguson "Witness 40"

-

Ferguson "Witness 40"

-

Ferguson "Witness 40"

-

Ferguson "Witness 40"

-

Ferguson "Witness 40"

-

Ferguson "Witness 40"

-

Ferguson "Witness 40"

-

Ferguson "Witness 40"

-

Ferguson "Witness 40"

-

Ferguson "Witness 40"

-

Ferguson "Witness 40"

-

Ferguson "Witness 40"

-

Ferguson "Witness 40"

12/16 UPDATE: Following the publication of this story, Sandra McElroy acknowledged to TSG that she is “Witness 40.” Voicing concerns for her minor children, McElroy said that she directed them to delete their Facebook accounts, adding that she has done the same. “After I speak with the prosecutor, attorney, and police if they say its alright I will call you,” she said. McElroy subsequently asked to have an off-the-record conversation, a request to which a TSG reporter agreed.

12/16 UPDATE: Following the publication of this story, Sandra McElroy acknowledged to TSG that she is “Witness 40.” Voicing concerns for her minor children, McElroy said that she directed them to delete their Facebook accounts, adding that she has done the same. “After I speak with the prosecutor, attorney, and police if they say its alright I will call you,” she said. McElroy subsequently asked to have an off-the-record conversation, a request to which a TSG reporter agreed.

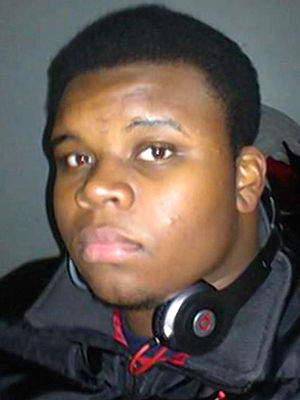

DECEMBER 15--The grand jury witness who testified that she saw Michael Brown pummel a cop before charging at him “like a football player, head down,” is a troubled, bipolar Missouri woman with a criminal past who has a history of making racist remarks and once insinuated herself into another high-profile St. Louis criminal case with claims that police eventually dismissed as a “complete fabrication,” The Smoking Gun has learned.

In interviews with police, FBI agents, and federal and state prosecutors--as well as during two separate appearances before the grand jury that ultimately declined to indict Officer Darren Wilson--the purported eyewitness delivered a preposterous and perjurious account  of the fatal encounter in Ferguson.

of the fatal encounter in Ferguson.

Referred to only as “Witness 40” in grand jury material, the woman concocted a story that is now baked into the narrative of the Ferguson grand jury, a panel before which she had no business appearing.

While the “hands-up” account of Dorian Johnson is often cited by those who demanded Wilson’s indictment, “Witness 40”’s testimony about seeing Brown batter Wilson and then rush the cop like a defensive end has repeatedly been pointed to by Wilson supporters as directly corroborative of the officer’s version of the August 9 confrontation. The “Witness 40” testimony, as Fox News sees it, is proof that the 18-year-old Brown’s killing was justified, and that the Ferguson grand jury got it right.

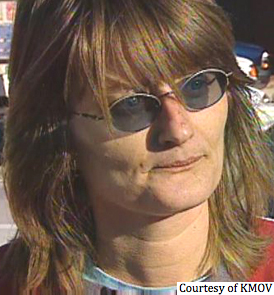

However, unlike Johnson, “Witness 40”--a 45-year-old St. Louis resident named Sandra McElroy--was nowhere near Canfield Drive on the Saturday afternoon Brown was shot to death.

Though prosecutors have sought to cloak the identity of grand jury witnesses, a TSG investigation has identified McElroy as “Witness 40.” A careful analysis of information contained in the unredacted portions of “Witness 40”’s grand jury testimony helped reporters identify McElroy and then conclusively match up details of her life with those of “Witness 40.”

TSG examined criminal, civil, matrimonial, and bankruptcy court records, as well as online postings and comments to unmask McElroy as “Witness 40,” the fabulist whose grand jury testimony and law enforcement interviews are deserving of multi-count perjury indictments.

McElroy did not reply to an e-mail seeking comment about her testimony. Messages sent yesterday to her three Facebook pages also went unanswered. Also, a message left on a phone number linked to McElroy was not returned.

Since the identities of grand jurors--as well as details of their deliberations--remain secret, there is no way of knowing what impact McElroy’s testimony had on members of the panel, which subsequently declined to vote indictments against Wilson. That decision  touched off looting and arson in Ferguson, about 30 miles from the apartment the divorced McElroy shares with her three daughters.

touched off looting and arson in Ferguson, about 30 miles from the apartment the divorced McElroy shares with her three daughters.

* * *

Sandra McElroy did not provide police with a contemporaneous account of the Brown-Wilson confrontation, which she claimed to have watched unfold in front of her as she stood on a nearby sidewalk smoking a cigarette.

Instead, McElroy (seen at left) waited four weeks after the shooting to contact cops. By the time she gave St. Louis police a statement on September 11, a general outline of Wilson’s version of the shooting had already appeared in the press. McElroy’s account of the confrontation dovetailed with Wilson’s reported recollection of the incident.

In the weeks after Brown’s shooting--but before she contacted police--McElroy used her Facebook account to comment on the case. On August 15, she “liked’ a Facebook comment reporting that Johnson had admitted that he and Brown stole cigars before the confrontation with Wilson. On August 17, a Facebook commenter wrote that Johnson and others should be arrested for inciting riots and giving false statements to police in connection with their claims that Brown had his hands up when shot by Wilson. “The report and autopsy are in so YES they were false,” McElroy wrote of the “hands-up” claims. This appears to be an odd comment from someone who claims to have been present during the shooting. In response to the posting of a news report about a rally in support of Wilson, McElroy wrote on August 17, “Prayers, support God Bless Officer Wilson.”

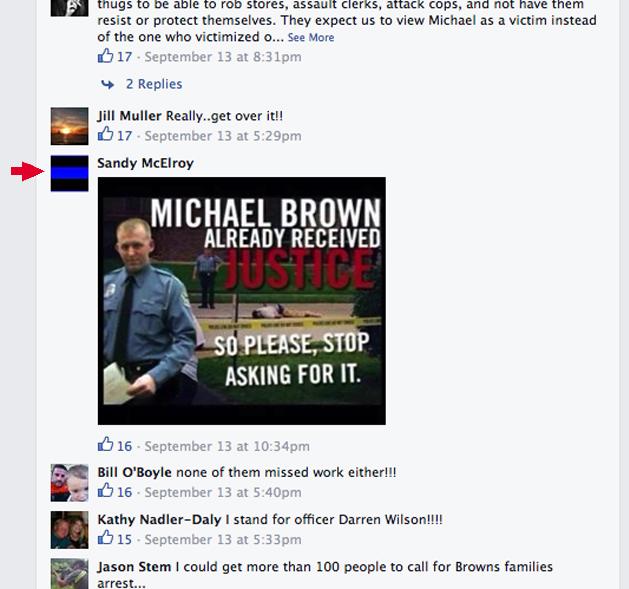

After meeting with St. Louis police, McElroy continued monitoring the case and posting online. Commenting on a September 12 Riverfront Times story reporting that Ferguson city officials had yet to meet with Brown’s family, McElroy wrote, “But haven’t you heard the news, There great great great grandpa may or may not have been owned by one of our great great great grandpas 200 yrs ago. (Sarcasm).” On September 13, McElroy went on a pro-Wilson Facebook page and posted a graphic that included a photo of Brown lying dead in the street. A type overlay read, “Michael Brown already received justice. So please, stop asking for it.” The following week  McElroy responded to a Facebook post about the criminal record of Wilson’s late mother. “As a teenager Mike Brown strong armed a store used drugs hit a police officer and received Justis,” she stated.

McElroy responded to a Facebook post about the criminal record of Wilson’s late mother. “As a teenager Mike Brown strong armed a store used drugs hit a police officer and received Justis,” she stated.

On October 22, McElroy went to the FBI field office in St. Louis and was interviewed by an agent and two Department of Justice prosecutors. The day before that taped meeting, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch published a lengthy story detailing exactly what Wilson told police investigators about the Ferguson shooting.

McElroy provided the federal investigators with an account that neatly tracked with Wilson’s version of the fatal confrontation. She claimed to have seen Brown and Johnson walking in the street before Wilson encountered them while seated in his patrol car. She said that the duo shoved the cruiser’s door closed as Wilson sought to exit the vehicle, then watched as Brown leaned into the car and began raining punches on the cop. McElroy claimed that she heard gunfire from inside the car, which prompted Brown and Johnson to speed off. As Brown ran, McElroy said, he pulled up his sagging pants, from which “his rear end was hanging out.”

But instead of continuing to flee, Brown stopped and turned around to face Wilson, McElroy said. The unarmed teenager, she recalled, gave Wilson a “What are you going to do about it look,” and then “bent down in a football position…and began to charge at the officer.” Brown, she added, “looked like he was on something.” As Brown rushed Wilson, McElroy said, the cop began firing. The “grunting” teenager, McElroy recalled, was hit with a volley of shots, the last of which drove Brown “face first” into the roadway.

McElroy’s tale was met with skepticism by the investigators, who reminded her that it was a crime to lie to federal agents. When questioned about inconsistencies in her story, McElroy was resolute about her vivid, blow-by-blow description of the deadly Brown- Wilson confrontation. “I know what I seen,” she said. “I know you don’t believe me.”

Wilson confrontation. “I know what I seen,” she said. “I know you don’t believe me.”

When asked what she was doing in Ferguson--which is about 30 miles north of her home--McElroy explained that she was planning to “pop in” on a former high school classmate she had not seen in 26 years. Saddled with an incorrect address and no cell phone, McElroy claimed that she pulled over to smoke a cigarette and seek directions from a black man standing under a tree. In short order, the violent confrontation between Brown and Wilson purportedly played out in front of McElroy.

Despite an abundance of red flags, state prosecutors put McElroy in front of the Ferguson grand jury the day after her meeting with the federal officials. After the 12-member panel listened to a tape of her interview conducted at the FBI office, McElroy appeared and, under oath, regaled the jurors with her eyewitness claims.

McElroy’s grand jury testimony came to an abrupt end at 2:30 that afternoon due to obligations of some grand jurors. But before the panel broke for the day, McElroy revealed that, “On August 9th after this happened when I got home, I wrote everything down on a piece of paper, would that be easier if I brought that in?”

“Sure,” answered prosecutor Kathi Alizadeh.

“Because that’s how I make sure I don’t get things confused because then it will be word for word,” said McElroy, who did not bother to mention her journaling while speaking a day earlier with federal investigators.

McElroy would return to the Ferguson grand jury 11 days later, journal pages in hand and with a revamped story for the panel.

* * *

Sandra McElroy was born in 1969 to a 17-year-old Tennessee girl. Her father was a 27-year-old truck driver married to another woman. McElroy was subsequently adopted by a Missouri couple, and she has mostly lived in St. Louis since she was a child. According to her grand jury testimony, she was diagnosed as bipolar when she was 16, but has not taken medication for the condition for about 25 years.

According to court records, McElroy was divorced in 2009 from Michael McElroy, a National Park Service employee with whom she had three daughters. She is also the mother of two sons, both in their early 20s.

In 2004, the couple filed for bankruptcy protection, ultimately listing debts in excess of $152,000, and assets totaling $16,575 (the pair valued the family’s guinea pigs at $20). The McElroys’s court petition reported that Brenda was disabled and received $564 monthly from the Social Security Administration.

The McElroy liabilities included two dozen unpaid medical bills dating to 2002, the year the couple filed a personal injury lawsuit in connection with a February 2001 auto accident in St. Louis. “Witness 40” told grand jurors that she was seriously injured in a car crash on Valentine’s Day in 2001. The witness, who said she was catapulted through the windshield, testified that she has struggled with a faulty memory since the accident.

The McElroy bankruptcy filings were standard Chapter 13 fare, until the filing of a remarkable 2005 motion by the couple’s attorney.

The McElroy bankruptcy filings were standard Chapter 13 fare, until the filing of a remarkable 2005 motion by the couple’s attorney.

The lawyer, Tracy Brown, sought court permission to withdraw from the bankruptcy case due to Sandra McElroy’s behavior. Brown advised the court that McElroy had frequently called her office and berated a secretary. McElroy, Brown wrote, “repeatedly used profanity when speaking with Counsel’s secretary,” adding that the diatribes “escalated to the use of racial slurs.”

Brown’s withdrawal motion was immediately approved by the federal judge handling the McElroy bankruptcy.

An examination of McElroy’s YouTube page, which she apparently shares with one of her daughters, reveals other evidence of racial animus. Next to a clip about the disappearance of a white woman who had a baby with a black man is the comment, “see what happens when you bed down with a monkey have ape babies and party with them.” A clip about the sentencing of two black women for murder is captioned, “put them monkeys in a cage.”

McElroy’s YouTube page is also filled with a variety of anti-Barack Obama videos, including a clip purporting to show Michelle Obama admitting that the president was born in Kenya. Over the past year, McElroy has subscribed to three channels devoted to mystery and  real crime shows, as well as a “We Are Darren Wilson” video channel.

real crime shows, as well as a “We Are Darren Wilson” video channel.

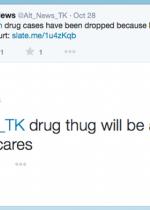

McElroy has rarely used her Twitter account, though she did post a message in late-October in response to a news report that several Ferguson drug cases had to be dropped because Darren Wilson failed to show up for court hearings. “drug thug will be arrested again who cares,” wrote McElroy.

Her inaugural tweet came in October 2013 in reply to an Obama swipe posted by Senator Ted Cruz. “Keep fighting, I am a government employee on furlough and I say keep it shut down. NO obama care please don't stop,” McElroy tweeted to the Texas Republican.

* * *

A review of court records shows that McElroy’s legal history is filled with a variety of civil lawsuits--often for failing to pay rent and other bills--as well as a 2007 criminal case. McElroy was arrested that year on two felony bad check charges. She pleaded guilty the following year to both counts and received a suspended sentence. The files on McElroy’s case have been sealed, a St. Louis court clerk told TSG.

During her grand jury testimony, “Witness 40” revealed that she pleaded guilty to a pair of felony “check fraud” charges in 2007. She recalled being sentenced to three years probation as part of an “SIS” (suspended imposition of sentence). “Witness 40” explained that she accidentally passed the bad checks after “I grabbed a black checkbook instead of a brown checkbook or a blue checkbook.” She copped to the charges, “Witness 40” added, because her father “taught me before he passed away regardless, you always tell the truth and you always admit to whatever, if it’s the truth.”

McElroy’s devotion to the truth--lacking during her appearances before the Ferguson grand jury--was also absent in early-2007 when she fabricated a bizarre story in the wake of the rescue of Shawn Hornbeck, a St. Louis boy who had been held captive for more than  four years by Michael Devlin, a resident of Kirkwood, a city just outside St. Louis.

four years by Michael Devlin, a resident of Kirkwood, a city just outside St. Louis.

McElroy, who also lived in Kirkwood, told KMOV-TV that she had known Devlin (seen at left) for 20 years. She also claimed to have gone to the police months after the child’s October 2002 disappearance to report that she had seen Devlin with Hornbeck. The police, McElroy said, checked out her tip and determined that the boy with Devlin was not Hornbeck.

In the face of McElroy’s allegations, the Kirkwood Police Department fired back at her. Cops reported that they investigated her claim and determined that “we have no record of any contact with Mrs. McElroy in regards to Shawn Hornbeck.” The police statement concluded, “We have found that this story is a complete fabrication.”

Undeterred by that withering blast, McElroy peddled another story to police in nearby Lincoln County, where Charles Arlin Henderson, 11, went missing in 1991. According to news reports, McElroy claimed that Devlin had given her photos he took of young boys, one of whom she knew as “Chuck” or “Chuckie.” Those images were shown to the missing boy’s mother, who said that while one of the boys in the photos resembled her son, “I’m keeping my emotions in check. I’m not going to be hurt anymore.”

A law enforcement task force investigated Devlin’s possible involvement in other missing children cases, but concluded that his only victims were Hornbeck and a 13-year-old boy who was abducted four days before Devlin’s arrest. Henderson, who has never been found, would now be 34-years-old.

* * *

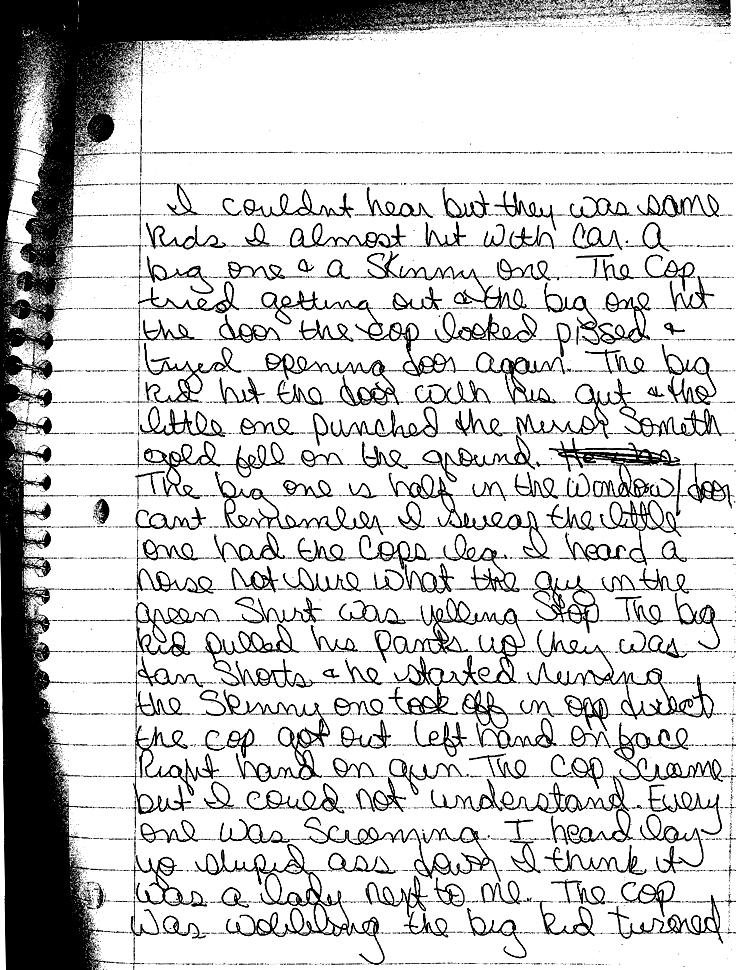

When Sandra McElroy returned to the Ferguson grand jury on November 3, she brought a spiral notebook purportedly containing her handwritten journal entries for some dates in August, including the Saturday Michael Brown was shot.

Before testifying about the content of her notebook scribblings, McElroy admitted that she had not driven to Ferguson in search of an African-American pal she had last seen in 1988. Instead, McElroy offered a substitute explanation that was, remarkably, an even bigger lie.

McElroy, again under oath, explained to grand jurors that she was something of an amateur urban anthropologist. Every couple of weeks, McElroy testified, she likes to “go into all the African-American neighborhoods.” During these weekend sojourns--apparently conducted when her ex has the kids--McElroy said she will “go in and have coffee and I will strike up a conversation with an African-American and I will try to talk to them because I’m trying to understand more.”

As she testified, McElroy admitted that her sworn account of the Brown-Wilson confrontation was likely peppered with details of the incident she had read online. But she remained adamant about having been on Canfield Drive and seeing Brown “going after the officer like a football player” before being shot to death.

As she testified, McElroy admitted that her sworn account of the Brown-Wilson confrontation was likely peppered with details of the incident she had read online. But she remained adamant about having been on Canfield Drive and seeing Brown “going after the officer like a football player” before being shot to death.

McElroy’s last two journal entries for August 9 read like an after-the-fact summary of the account she gave to federal investigators on October 22 and the Ferguson grand jury the following afternoon. It is so obvious that the notebook entries were not contemporaneous creations that investigators should have checked to see if the ink had dried.

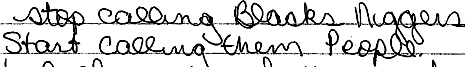

The opening entry in McElroy’s journal on the day Brown died declared, “Well Im gonna take my random drive to Florisant. Need to understand the Black race better so I stop calling Blacks Niggers and Start calling them People.” A commendable goal, indeed.

Near the end of her testimony, McElroy was questioned about a Facebook page she had started to raise money for Wilson. McElroy corrected a prosecutor, saying that the page was “not for Darren Wilson,” but rather other law enforcement officers who have “been  dealing with all the long hours” as a result of unrest in Ferguson.

dealing with all the long hours” as a result of unrest in Ferguson.

McElroy’s group purports to be a “non-profit organization,” though Missouri state corporation records contain no mention of the outfit, which launched its Facebook page two weeks after Brown’s killing. In donation pitches posted on other Facebook pages, “First Responders Support” claimed that money raised through an online fundraising campaign would be used to pay for care packages and gift cards for cops “that have been dealing with the riots here in St Louis MO.”

In an October 25 Facebook discussion thread on the web site of a St. Louis TV station, McElroy--using one of her personal Facebook accounts--posted a link to the “First Responders” fundraising page, along with a call to action. “How about support the LEO instead of these thugs,” she wrote. Two minutes later, a similar link to the YouCaring web site was posted from the “First Responders” Facebook account.

It is unknown how much money McElroy’s Facebook gambit has raised, or how the money was spent. But in a December 5 post, the “First Responders” page offered a fundraising update. Since “Officer Wilson’s attorney has made it clear there are to be NO online donation excepted,” McElroy wrote, “I purchased a money order and mailed it” to the “Darren Wilson Trust Fund.”

A TSG reporter last week sent a message to the “First Responders” Facebook page asking how much money the group raised and donated to Wilson. While that inquiry was ignored, the fundraising post was subsequently deleted.

Perhaps McElroy did not want to get caught telling a lie. (18 pages)