Inside The DEA's Hip-Hop Cocaine Investigation

Sealed records detail suspect’s brazen, bizarre acts

View Document

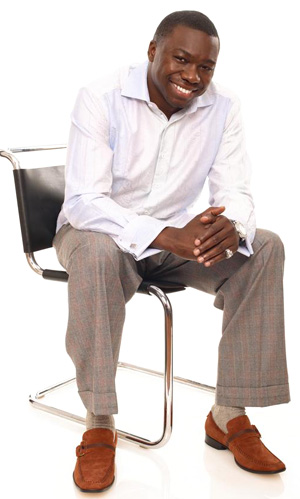

MAY 24--By the time he walked into a Kinko’s in Atlanta on December 29, Khalil Abdullah was well aware that he was in the crosshairs of the Drug Enforcement Administration. The 37-year-old New Jersey resident and several close associates, including rap music manager--and primary DEA target--James Rosemond, were the subjects of a sprawling, year-long federal probe into their suspected trafficking of hundreds of kilos of cocaine from Los Angeles to New York.

The narcotics, investigators determined, were initially sent via overnight courier services like Federal Express, but ring members later took to concealing cocaine inside “road cases” that were sent between recording studios on both coasts. Proceeds from the drug sales were sent west in vacuum-sealed bags, each of which held $100,000.

Federal prosecutors were methodically working their way up the group’s chain of command, and viewed Abdullah as a stepping stone to James Rosemond. “He is Jimmy’s man,” one lawyer familiar with the DEA probe told TSG. In the face of this government pressure, sealed court records reveal, Abdullah has engaged in a series of increasingly brazen and bizarre acts that have backfired miserably, resulting in his indictment and apparent decision to cooperate with law enforcement officials.

Federal prosecutors were methodically working their way up the group’s chain of command, and viewed Abdullah as a stepping stone to James Rosemond. “He is Jimmy’s man,” one lawyer familiar with the DEA probe told TSG. In the face of this government pressure, sealed court records reveal, Abdullah has engaged in a series of increasingly brazen and bizarre acts that have backfired miserably, resulting in his indictment and apparent decision to cooperate with law enforcement officials.

[Agents have secured an arrest warrant for Rosemond, but the music industry figure remains a fugitive at this writing. In a rambling statement released yesterday to a hip-hop web site, Rosemond proclaimed his innocence and claimed that he was preparing to surrender. His lawyer, Jeffrey Lichtman, declined to comment about the federal investigation.]

As the New Year approached, Abdullah, pictured above, knew that several men, including Rosemond’s brother Kesner, had already been arrested and charged as members of the distribution ring. More importantly, a major L.A. coke supplier named Henry “Black” Butler--a convicted felon whose brother-in-law, Lee Daniels, directed the Oscar-nominated film “Precious”--had flipped and was cooperating with the DEA and the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Brooklyn, where the probe was centered and a grand jury had been empaneled.

So, in anticipation of his own eventual collar, Abdullah--who was routinely in possession of upwards of $1 million in drug proceeds--hatched a scheme to skim some money from his co-conspirators before incarceration made that an impossibility. Inexplicably, Abdullah went to the Kinko’s and sent an “Urgent” fax to both the DEA’s New York field office as well as Brooklyn federal prosecutors (prior to hitting “send,” Abdullah had called the DEA to secure its fax number).

As detailed in a sealed April 25 U.S. District Court filing obtained by TSG, Abdullah’s letter--addressed “To Whom It May Concern”--reported that there was a music equipment case at a New York City recording studio that contained $650,000. The cash, the fax disclosed, was in “vacuum-sealed bags and ready to be shipped for the purpose of purchasing Narcotics in Los Angeles.”

The letter stated that if agents got to the studio before the case was picked up, “you can also get the name of the shipper and his company which is legitimate which in turn will lead you to the originator and owner of the money.” Recipients of the fax were also directed to contact federal prosecutor Todd Kaminsky and “Let him know this is relative to a major case he is working on. Once he see the word music he will know what this is regarding.”

The letter stated that if agents got to the studio before the case was picked up, “you can also get the name of the shipper and his company which is legitimate which in turn will lead you to the originator and owner of the money.” Recipients of the fax were also directed to contact federal prosecutor Todd Kaminsky and “Let him know this is relative to a major case he is working on. Once he see the word music he will know what this is regarding.”

The letter concluded, “Good Luck and more to follow.”

Following the receipt of the fax, DEA agents raced to the studio and seized the road case, discovering about $790,000. The money--including 30,463 20-dollar bills--was found inside “vacuum-sealed plastic in $100,000 bundles.” Investigators also observed “torn and empty vacuum-sealing on a shelf inside the case, suggesting that additional cash had been removed,” according to the sealed April 25 letter prepared by Kaminsky, who is leading the Department of Justice probe of the cocaine trafficking operation.

Surveillance camera footage from Kinko’s captured Abdullah sending the faxes, and his call to the DEA seeking the agency’s fax number was recorded (agents familiar with his voice identified him as the caller). In fact, Abdullah actually called drug agents a second time to confirm receipt of his fax.

Faced with Abdullah’s inexplicable behavior, federal investigators have theorized that, with the help of an associate named Rodolfo Fernandez, he alerted the DEA about the cash so that, pre-confiscation, he “could take a certain amount of it for himself” and then cover that theft by “telling his co-conspirators that the case was seized by law enforcement.”

Agents contend that the torn and empty bags found in the case likely contained cash swiped hours earlier by Abdullah and Fernandez, who left a federal prison in December 2009 after spending nearly nine years locked up for cocaine trafficking. At the time the fax was sent, Fernandez, 34, was in the midst of a five-year probation term and claimed to be working as a janitor, according to court filings.

When discovered by fellow narcotics traffickers, Abdullah’s sort of thieving treachery--not to mention his faxed acknowledgment that the seized money represented the proceeds from a drug dealing operation--would likely be met with severe repercussions. This drug world reality likely played a role in Fernandez’s decision--within just three weeks of his arrest--to plead guilty to a felony charge of conspiracy to distribute cocaine and, according to two sources, agree to cooperate with federal investigators.

A week after Fernandez’s plea, a grand jury returned a five-count indictment accusing Abdullah of cocaine trafficking, money laundering, and other felonies. On April 25, investigators arrested Abdullah near his Closter, New Jersey home as he was driving his 2011 BMW 750. In March, when DEA agents approached Abdullah while he was parked near his residence, they discovered about $30,000 in cash “resting on the seat inside the defendant’s vehicle and inside of his trunk.” The money was seized, since probers believed it represented proceeds of illegal narcotics sales.

A week after Fernandez’s plea, a grand jury returned a five-count indictment accusing Abdullah of cocaine trafficking, money laundering, and other felonies. On April 25, investigators arrested Abdullah near his Closter, New Jersey home as he was driving his 2011 BMW 750. In March, when DEA agents approached Abdullah while he was parked near his residence, they discovered about $30,000 in cash “resting on the seat inside the defendant’s vehicle and inside of his trunk.” The money was seized, since probers believed it represented proceeds of illegal narcotics sales.

According to lawyers familiar with the government probe, investigators believe that the leaders of the bi-coastal cocaine trafficking ring were Butler (Los Angeles) and James Rosemond (New York). The men are contemporaries--Butler is 44, Rosemond is 46--who both have lengthy raps sheets and have worked in the hip-hop industry.

In addition to distributing kilos of cocaine, Butler, pictured above, has worked as a music producer and run legitimate promotion companies, according to his lawyer. The Thousand Oaks resident once co-owned Mogul Media Group, a promotion firm, and a nightclub in Studio City. Photos on his now-defunct web site (and those distributed by Butler’s former PR firm) show him posing with singers Alicia Keys, Christina Aguilera, and Brian McKnight, and comedian Jamie Foxx.

Rosemond runs Czar Entertainment, whose web site lists rapper The Game, singers Sean Kingston and Brandy, and ex-boxer Mike Tyson as clients. Rosemond, nicknamed Jimmy Ace and Jimmy Henchman, is perhaps best known for the scorn once directed at him by Tupac Shakur on the song “Against All Odds.” The late rapper accused Rosemond of involvement in his November 1994 shooting at a Manhattan recording studio. Shakur, who survived that fusillade, was shot to death two years later in Las Vegas.

While Rosemond, pictured at left, was present that evening at Quad Studios near Times Square, he has repeatedly denied Shakur’s claim that he helped set up the rapper’s ambush. Remarkably, at the time of the shooting, Rosemond had been a fugitive for 15 months. In fact, it wasn’t until February 1996 that federal agents caught up to him at an L.A. hotel, where the pistol-happy Rosemond was found in possession of a .38 caliber Amadeo Rossi handgun.

While Rosemond, pictured at left, was present that evening at Quad Studios near Times Square, he has repeatedly denied Shakur’s claim that he helped set up the rapper’s ambush. Remarkably, at the time of the shooting, Rosemond had been a fugitive for 15 months. In fact, it wasn’t until February 1996 that federal agents caught up to him at an L.A. hotel, where the pistol-happy Rosemond was found in possession of a .38 caliber Amadeo Rossi handgun.

By comparison, Abdullah does not have identifiable music industry interests. Though he frequented recording studios--when cocaine and money were being packed up--Abdullah “does not work in the music industry and has instead operated businesses in the security industry as well as the hair-extension industry over the past several years,” according to a court filing by federal prosecutors.

Abdullah shares a New Jersey address with Amoy Pitters, a celebrity hairstylist whose clients have included Naomi Campbell, Rihanna, Alicia Keys, and Mary J. Blige. Pitters, who has widely been described as an “extensions expert,” declined to answer questions about Abdullah when reached on her cell phone. As seen below, Abdullah and Pitters were photographed together last year when they attended the opening of Pitters’s Manhattan hair salon.

Like most of the cocaine ring’s members, Abdullah is a convicted felon who has spent time behind bars (two years for a robbery collar). In September 2008, he was arrested for shooting another man, though that case was subsequently dismissed. In debriefings, Fernandez has told DEA agents that Abdullah confided that he “paid the victim to drop the charges.”

Sources described Abdullah as a key deputy to Rosemond. For example, when Butler was arrested last August and transported from Los Angeles to New York to face charges, Rosemond dispatched Abdullah to secure legal counsel for Butler, according to a source.

A sealed U.S. District Court filing reveals that Abdullah--calling himself “Mike”--hired Long Island attorney Jason Russo and paid the lawyer’s retainer from a “large bag of cash” that was in his vehicle. During his initial meeting with Russo, Abdullah provided the attorney with a piece of paper containing questions that he wanted the defense lawyer to ask Butler, who was then locked up in the Nassau County jail.

A sealed U.S. District Court filing reveals that Abdullah--calling himself “Mike”--hired Long Island attorney Jason Russo and paid the lawyer’s retainer from a “large bag of cash” that was in his vehicle. During his initial meeting with Russo, Abdullah provided the attorney with a piece of paper containing questions that he wanted the defense lawyer to ask Butler, who was then locked up in the Nassau County jail.

One of the questions for Butler, a source told TSG, sought to determine if federal agents had questioned him about Rosemond, referred to as “J” in the note. The note also referred to Rosemond’s brother--who, like Butler, was also jailed as part of the cocaine distribution outfit--as “K.”

The piece of paper Abdullah gave Russo “exhorted” Butler “not to cooperate with the government,” according to the sealed filing. Abdullah’s message for Butler stated: “Lastly, stay firm, cuz the quantity is small. They gonna try to trick you to talk but don’t. Also, K is not talking. So don’t give them more than they already have.”

However, despite the call to “stay firm,” Butler and Russo subsequently met secretly with DEA agents and prosecutors to begin shaping the outlines of a cooperation agreement. During this proffer session, Butler described his role in the trafficking conspiracy and detailed the involvement of other suspects. While his client was debriefed, Russo took notes in a notebook, with the final entry indicating the date and time of Butler’s next scheduled proffer session in the U.S. Attorney’s office.

While Butler’s meetings with law enforcement were held in secret, Abdullah “apparently received information that [Butler] had begun to cooperate with the government,” according to a sealed court filing. Abdullah, visibly upset, showed up last October at Russo’s office and demanded to know if Butler had flipped.

When Russo denied that his client was cooperating, Abdullah accused the 39-year-old attorney of lying to him. Abdullah then confronted Russo with a copy of the attorney’s own notes from the Butler proffer session. Abdullah also told Russo that he knew the date of Butler’s next debriefing with federal investigators. Challenging Russo’s denial that Butler was cooperating, Abdullah stated that “if it were true, he would expect to find the Defense Attorney in his office on the date of the upcoming meeting.” Russo, prosecutors noted, understood this to mean that Abdullah “would surveil” him to “ensure that he did not attend a proffer meeting.”

When Russo denied that his client was cooperating, Abdullah accused the 39-year-old attorney of lying to him. Abdullah then confronted Russo with a copy of the attorney’s own notes from the Butler proffer session. Abdullah also told Russo that he knew the date of Butler’s next debriefing with federal investigators. Challenging Russo’s denial that Butler was cooperating, Abdullah stated that “if it were true, he would expect to find the Defense Attorney in his office on the date of the upcoming meeting.” Russo, prosecutors noted, understood this to mean that Abdullah “would surveil” him to “ensure that he did not attend a proffer meeting.”

Concerned for his safety as well as Butler’s, Russo contacted federal prosecutors and detailed his contacts with Abdullah. The lawyer provided investigators with the “stay firm” note he had initially been given by Abdullah and told of being paid in cash by Rosemond’s crony.

Russo also shared with investigators a text message Abdullah sent to him the day after the confrontation in his law office. “Do what’s in your best judgement,” Abdullah wrote. “Just don’t flip on me with those people pls.” In a subsequent recorded telephone conversation, Russo claimed to Abdullah that he would no longer represent Butler (which was not true). A relieved Abdullah responded, “My man.”

In light of his alleged attempt to keep Butler from assisting the DEA investigation, Abdullah was hit with an obstruction of justice rap, one of the five felony charges included in Abdullah’s April 25 indictment.

In an interview, Russo told TSG that the difficult decision to assist investigators was solely “borne out of a fear for my own safety.”

Asked how Abdullah could have obtained his notes from the Butler proffer session, Russo said that he only shared them with one person, a California defense attorney who had previously represented Butler. That lawyer, Roger Rosen, did not return phone messages left at his Los Angeles office, nor did he respond to a detailed e-mail seeking comment as to whether he shared the confidential notes with another party.

Asked how Abdullah could have obtained his notes from the Butler proffer session, Russo said that he only shared them with one person, a California defense attorney who had previously represented Butler. That lawyer, Roger Rosen, did not return phone messages left at his Los Angeles office, nor did he respond to a detailed e-mail seeking comment as to whether he shared the confidential notes with another party.

In 2007, the 66-year-old Rosen, pictured at right, defended music producer Phil Spector against murder charges; the case ended in a mistrial when the jury deadlocked 10-2 in favor of conviction.

The puzzle of how Abdullah came into possession of Russo’s notes has been of great interest to federal officials, considering that the leak--a possible attempt at obstructing justice--could have jeopardized the life of a government witness.

Abdullah, of course, would know where he got Russo’s confidential notes. If convicted for his alleged “leadership role” in the cocaine distribution scheme, Rosemond’s sidekick, prosecutors estimate, would face between 22 and 27 years in prison based on federal sentencing guidelines.

That unappetizing prospect may have caused Abdullah to join Fernandez and Butler in the warm embrace of Uncle Sam. Until May 9, when he appeared in federal court for a status conference on his case, Abdullah was in custody at the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn, according to Bureau of Prisons computerized records. Since that date, however, his BoP status has been listed as “released.”

Since court records do not show Abdullah being freed via bail, his prison status change is likely a reflection that he has either been placed in a protective unit or turned over to the custody of a law enforcement agency (like, say, the DEA). A one-page memo docketed after the May 9 hearing reported that Abdullah and prosecutors “are beginning discovery and negotiations.”

Abdullah’s lawyer, Anthony Ricco, did not respond to numerous messages left at his Manhattan office. Ricco also did not respond to an e-mail seeking comment about allegations leveled against Abdullah, his custody status, and his possible government cooperation. (11 pages)

Comments (1)