Trump Once Looked For The Union Label

Before Deutsche Bank, tycoon received labor loans

![]()

APRIL 9--As the story goes, when defaults, bankruptcies, and assorted chicanery left Donald Trump a late-90s Wall Street outcast, he found shelter in the welcoming arms of Deutsche Bank, the only financial institution then willing to risk lending money to the dodgy developer.

While Trump’s dealings with the German multinational--which have continued for 20 years--are now the subject of investigations by two House of Representatives committees and the New York State Attorney General’s Office, there was actually another institution that first lent the toxic Trump money in the wake of the financial beating the real estate tycoon inflicted on his many creditors and bondholders.

Beginning in early-1995, the Union Labor Life Insurance Company, or ULLICO, was involved in loans to Trump totaling nearly $350 million, according to mortgage filings in New York and Florida.  Over a five-year period, ULLICO made eight separate loans to Trump covering three of his properties: the Mar-a-Lago club in Palm Beach, the 40 Wall Street office tower in Manhattan, and a supertall condominium development across from the United Nations (seen above).

Over a five-year period, ULLICO made eight separate loans to Trump covering three of his properties: the Mar-a-Lago club in Palm Beach, the 40 Wall Street office tower in Manhattan, and a supertall condominium development across from the United Nations (seen above).

The ULLICO loans carried the hint of corruption that has become synonymous with the business practices of Trump and his development organization. The transactions were tainted by questionable benefits provided by Trump to an influential union official and the use of Trump’s now-shuttered charitable foundation as a source of improper slush fund payments to a group controlled by the labor leader.

Founded by labor organizations as a vehicle through which their pension monies could be invested, ULLICO stakeholders include nearly all public- and private-sector unions, from Teamsters and teachers to steelworkers and social workers. In 1977, ULLICO began offering construction loans to developers, a method by which to optimize investment returns while also creating union jobs in the building trades industry.

In retrospect, the ULLICO loans to Trump are now likely a sore spot for the organization, considering that the developer-turned-president has become openly hostile to organized labor. In addition to his support for right-to-work laws, Trump has signed executive orders intended to cut civil service protections. Trump celebrated Labor Day last year by attacking Richard Trumka, the AFL-CIO president. In a tweet, Trump accused Trumka of poorly representing his members during a Fox News Channel interview during which Trumka criticized Trump. “It is easy to see why unions are doing so poorly,” Trump wrote. He added, “A Dem!”

At the time of the 1990s ULLICO loans, Trump had a mixed record with labor. While he had little choice but to employ union workers at construction sites in New York City and Atlantic City, New Jersey, Trump famously used a crew of 200 undocumented Polish workers to handle demolition work on the Fifth Avenue site where Trump Tower now stands. Working 12-hour shifts without proper safety equipment, some members of the so-called Polish Brigade were paid as little as $4 an hour. In 1998--after 15 years of litigation--Trump eventually paid $1.375 million to settle a  lawsuit that accused him of stiffing a union pension fund by hiring the undocumented workers.

lawsuit that accused him of stiffing a union pension fund by hiring the undocumented workers.

ULLICO’S first loan to Trump came in early-1995, when the union group provided the Mar-a-Lago club with $10 million, according to property records. Trump, who purchased the Palm Beach resort in 1985, subsequently received two other loans--totaling $25 million--from ULLICO. Trump personally guaranteed the Mar-a-Lago loans, which included a provision requiring him to obtain a key man life insurance policy covering ULLICO in the event Trump died while the debt remained outstanding. The Mar-a-Lago loans were paid off in late-2008, mortgage records show.

Following Trump’s purchase of 40 Wall Street in late-1995, ULLICO gave the developer $10 million in July 1996 and an additional $8 million in April 1997. Construction loan documents included a ULLICO rider requiring the mortgage recipient to only employ contractors and subcontractors with collective bargaining agreements with the AFL-CIO’s Building Trades Department. The two ULLICO loans were subsequently assigned in April 1998 to a Deutsche Bank subsidiary, which loaned Trump an additional $130 million to renovate the lower Manhattan office tower.

ULLICO’s largest loans to Trump came in connection with the builder’s development of Trump World Tower, a 72-story condominium steps from United Nations headquarters. In a series of 1998 construction loans, ULLICO and a co-lender provided the Trump project with $295 million, according to mortgage filings. Like 40 Wall Street, the loan documents included ULLICO’s union labor rider. Upon completion of the residential tower, Deutsche Bank bought the consolidated loan from ULLICO and its partner, the German bank Hypovereinsbank.

Like 40 Wall Street (seen at right), the Trump World Tower development was a “money fountain” for Trump and his partners, according to a former Deutsche Bank official who estimated that the tycoon  personally made upwards of $500 million on the condo project.

personally made upwards of $500 million on the condo project.

The only glitch that emerged as financing was arranged was the question of what would happen to the condo development in the face of a union strike. Trump, the ex-Deutsche Bank executive recalled, “came up with a ‘no strike’ letter from the major unions, which I’d never seen.” Signed by representatives of every trade union on the site, the letter pledged that members would show up to work “even if a general strike was called by the union,” the former banker said.

After a series of financial disasters, including casino bankruptcies, the failure of the Trump Shuttle airline, and the loss of the landmark Plaza Hotel in a Chapter 11 proceeding, the 40 Wall Street and Trump World Tower deals showed that Trump could still identify, assemble, and develop lucrative Manhattan building sites.

Trump’s financial resurrection was aided by ULLICO mortgages that were largely the handiwork of a powerful New York City labor official who proudly took credit for securing the loans.

Like his father, Edward Malloy was a steamfitter by trade. A Manhattan native and Army veteran, Malloy would eventually run a steamfitters local before being elected in 1992 to head the powerful Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York (as well as its statewide counterpart). Malloy ran the state’s largest private-sector union, which had more than 200,000 members.

With a combined salary approaching $250,000, Malloy was one of the most influential figures in the New York City construction industry for two decades. In mid-1998, when New York City officials announced that a $120 million film and TV complex was being financed by ULLICO, Malloy was identified as a ULLICO vice president and president of the construction trades council. Malloy was also CEO of a consulting company that was incorporated from his Manhattan home in October 2002, though the firm’s clients and the nature of its business is unknown.

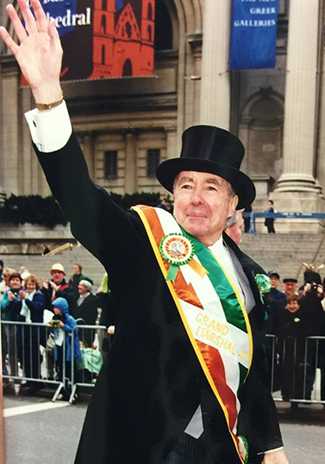

When Malloy was named Grand Marshal of the 2001 St. Patrick’s Day Parade, Trump saluted him as a “great guy” and “one of the finest human beings you’ll ever meet.” In 2012, when Malloy died of cancer at age 77, Trump attended the labor leader’s wake and his funeral mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Malloy’s widow recalled that Trump, who affectionately called her husband “Blue  Eyes,” arrived at both services without a bodyguard. “My husband was very fond of him,” said Marilyn Malloy.

Eyes,” arrived at both services without a bodyguard. “My husband was very fond of him,” said Marilyn Malloy.

The nature of Trump’s relationship with Malloy was first examined by the late Wayne Barrett in a 2001 Village Voice story about the questionable finances of the National Museum of Catholic Art and History, a New York City not-for-profit group.

The organization, Barrett reported, was launched by Christina Cox, a former model/actress/Playboy Bunny who used the group as a veritable ATM. Cox’s activities triggered a state investigation that ended with her agreeing to repay nearly $90,000 for “inappropriate and extravagant” personal expenses that were footed by the not-for-profit. The Catholic outfit would go on to raise millions of dollars, open a rarely visited museum in Manhattan’s East Harlem, and crash into bankruptcy in early-2012.

While Cox, now 67, was the museum’s founder and executive director, its key officer was Malloy, the group’s chairman and its chief fundraiser. The married Malloy was also Cox’s boyfriend, a relationship that spanned many years, according to two sources familiar with the museum’s operation. Reached Sunday, Cox declined to answer questions about her relationship with Malloy. Cox, who lives in Washington, D.C., excused herself from the phone by saying, “I’m on my way out to attend a five o’clock mass.”

In addition to drumming up grants from a variety of elected officials, Malloy got contractors to perform free work at the museum, secured a $1 million ULLICO loan for the organization, and donated $10,000 from his own union’s funds.

Asked about Malloy’s involvement with the group, a former museum official described it as “Eddie’s little pet project to keep his girlfriend happy and to fund her some way.” When the museum filed for bankrupty protection, Malloy was said to be personally owed nearly $33,000 for “Storage Fees for Debtor Property.”

At the same time Malloy was helping Trump secure ULLICO financing for Mar-a-Lago and the two Manhattan projects, the developer was donating money to the Catholic museum boondoggle.

The contributions, of course, came from the Donald J. Trump Foundation, which agreed to dissolve last year in the face of a blistering lawsuit brought by the New York State Attorney General. The AG alleged that Trump’s foundation engaged in a “shocking  pattern of illegality” and functioned as “little more than a checkbook to serve Mr. Trump’s business and political interests.”

pattern of illegality” and functioned as “little more than a checkbook to serve Mr. Trump’s business and political interests.”

The donations to the museum from the Trump slush fund totaled $122,000, according to IRS filings. Among the seven donations--which were given between 1995 and 2002--were $50,000 contributions in 1995 and 1999 (among the biggest donations ever coughed up the shuttered foundation). The checks from Trump--who is not Catholic, a fan of museums, or an artifacts enthusiast--dovetail with the receipt of ULLICO loans for which Malloy took credit.

When asked about whether he pulled strings to secure union loans for Trump, Malloy once replied, “Sure. I’m trying to get my people work. That’s business, and it’s legal.” Cox is pictured above awarding Trump a crystal cross during a museum fundraiser at the Friars Club in Manhattan.

In addition to donating money to Malloy’s pet museum project, Trump often hosted the union leader at Mar-a-Lago. With his mistress in tow, Malloy appeared to visit the Florida resort so frequently that staff took to referring to Cox as “Mrs. Malloy,” according to a source who traveled to Mar-a-Lago with the couple. In addition to comping Malloy’s stays, Trump would sometimes transport the union boss to and from Palm Beach on his Boeing 727.

After a long weekend trip in early-2000, Malloy and Cox returned to New York with Trump on the developer’s jet. During the Sunday flight, a source onboard recalled, Trump “pontificated” on the subject of Malloy’s power, saying the union boss could get tens of thousands of workers to strike by “lifting his finger.”

When the Voice’s Barrett asked Malloy about his Mar-a-Lago excursions, the union official acknowledged taking a few free trips there with Cox (though he declined to discuss their sleeping arrangements). Two sources, however, said Malloy and Cox were more frequent visitors to Mar-a-Lago. A former museum official recalled Cox saying that she and Malloy had “double-dated” with Trump and Marla Maples, the developer’s second wife.

Trump invited Malloy and his wife to the developer’s January 2005 marriage to Melania Knauss. Malloy alone attended the lavish Palm Beach affair, whose guest list included Bill and Hillary Clinton, P. Diddy, Simon Cowell, and Rudolph Giuliani.

In addition to the loans shepherded by Malloy, ULLICO was among a consortium of lenders that took a piece of a $640 million mortgage syndicated by Deutsche Bank in connection with Trump’s construction of a 92-story Chicago skyscraper. When Trump subsequently defaulted on the loan, he filed a $3 billion lawsuit in 2008 against Deutsche Bank, ULLICO, and other lenders claiming that the defendants somehow undermined the project and harmed his reputation by demanding to get paid.

The lawsuit was settled in 2010 when Deutsche Bank, ULLICO, and the other defendants agreed to a restructuring of Trump’s debt. While the litigation was still pending, a ULLICO executive who negotiated the Chicago loan (as well as the Malloy mortgages) was a guest of Trump’s at the October 2009 wedding of his daughter Ivanka to Jared Kushner.

Despite being sued by Trump, Deutsche Bank eventually resumed lending him money. It does not appear, however, that ULLICO--whose loan portfolio has included more than 500 projects and over $16 billion in financings--has since made any other loans to Trump, either as a primary lender or part of a syndicate.